Plants Alongside and Inside Rivers

Flowing waters constitute a significant ecological habitat. Plants residing here are adapted to the year-round influence of freshwater. The quality of flowing water, the diversity of currents, and the dynamics of water levels profoundly shape the ecosystem. The richer the habitat, the greater the variety of plants and animals it supports.

By the Water’s Edge

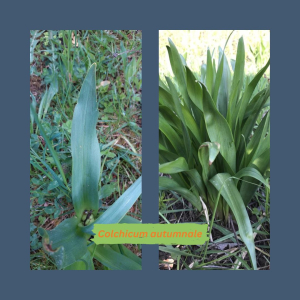

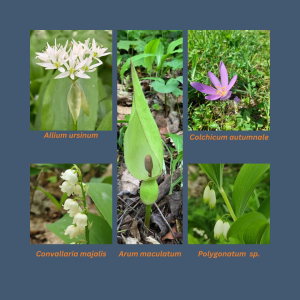

At the water’s edge and on embankments, various plant families thrive. Many of these plants have narrow, elongated leaves. Well-known examples include the Yellow Iris (Iris pseudacorus) and the Water Avens (Geum rivale), which bloom in late spring. From June to early September, you can find Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) and Meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria). In reed beds, you’ll find Branched Bur-reed (Sparganium erectum) and Narrow-leaved Reedmace (Typha angustifolia). On the damp shoreline, species typical of wetlands can be found, such as Marsh Woundwort (Stachys palustris).

Underwater

Submerged aquatic plants grow within the water. They root in the waterbed and develop leaves underwater. However, their flowers and floating leaves reach the surface. In spring, in the cool temperatures of streams and rivers, these plants might not be very noticeable. But as the year progresses, leaves and flowers become evident. One typical species is the Floating Water Crowfoot (Ranunculus fluitans), characterizing an entire plant community. Other aquatic species include Arrowhead (Sagittaria sagittifolia), Water Starwort (Callitriche), and pondweeds like Floating Pondweed (Potamogeton natans).

Habitat Protection

Habitats along and within water bodies are delicate and vulnerable. Diversity is impacted by activities such as bank and riverbed stabilization, over-fertilization, drainage, channelization, low water levels, and improper maintenance. In Germany, the Bund für Umwelt und Naturschutz Deutschland (BUND) advocates for the enhancement and protection of sensitive habitats along flowing waters. The regional chapter in Saxony, as part of the “Sustainable Recovery” initiative by the Saxon Ministry for Energy, Climate Protection, Agriculture, and the Environment, is examining the potential for second-order watercourses in the rural areas of the Free State. The project aims to provide recommendations for landowners, residents, conservation organizations, and dedicated citizens.

This article was featured in the Flora-Incognita app as a story in the summer of 2023. The app provides intriguing information about plants, ecology, species identification, as well as tips and tricks for plant identification. Why not take a look?