Importance of Phenology

A new paper, published by the Flora Incognita Research Group, shows that the plant observations collected via Flora Incognita can support phenological monitoring initiatives. Why is that important?

Observing plant phenology helps scientists to understand how climate change affects plants, for example. If flowering periods shift due to changing climatic conditions, this can have significant consequences for ecological relationships or the spread of species. Traditionally, the phases of phenology (e.g. bud break, leaf-out, onset of flowering, and leaf senescence) are recorded manually by trained volunteers – but their numbers are steadily declining.

Traditional Phenology Monitoring

In Germany, mainly the German Weather Service conducts the “official” plant phenology monitoring (Deutscher Wetterdienst, DWD). Here, every observer is given a specific “station,” corresponding to a dedicated spot for observing one tree, shrub or herbaceous plant. The number of these stations varies depending on the observed species. This means that some species have more stations than others. During the growing season, observers need to check on the plants they are studying at least two times each week and record the day when specific pheno phases begin.

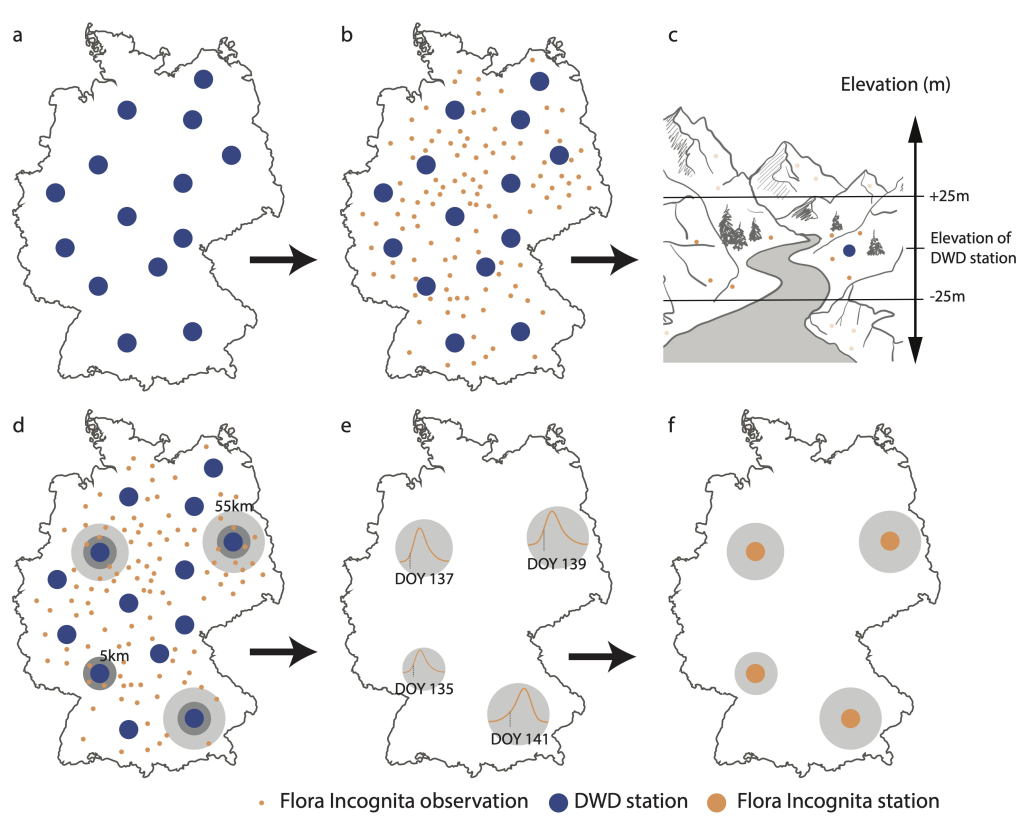

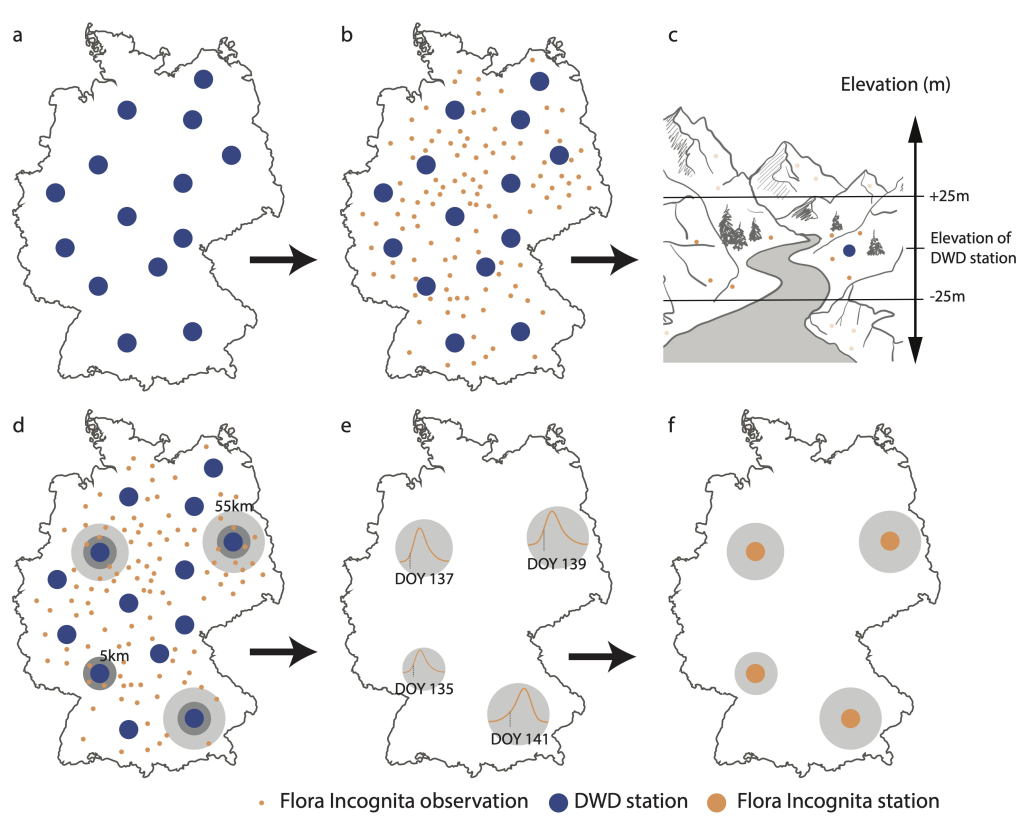

Process diagram, showing how plant observation data are converted into onset of flowering dates and related to DWD (German meteorological service) observation stations for one examplary species. (from: Katal & Rzanny et al. 2023)

Processing Flora Incognita data

The new paper’s lead authors Negin Katal and Michael Rzanny found a way to process Flora Incognita data in a way that they resemble DWD stations: They identified the locations of the DWD stations, and for each species, created a 5 km circle around them. Within this circle, they collected all the Flora Incognita observations for that species within a certain altitude range. At least 35 of those opportunistic records were needed to create a “Flora Incognita station”. If those could not be reached, even within an additional buffer (1 km at a time, up to 55 km), no Flora Incognita station was established at that location.

Interpolation of data

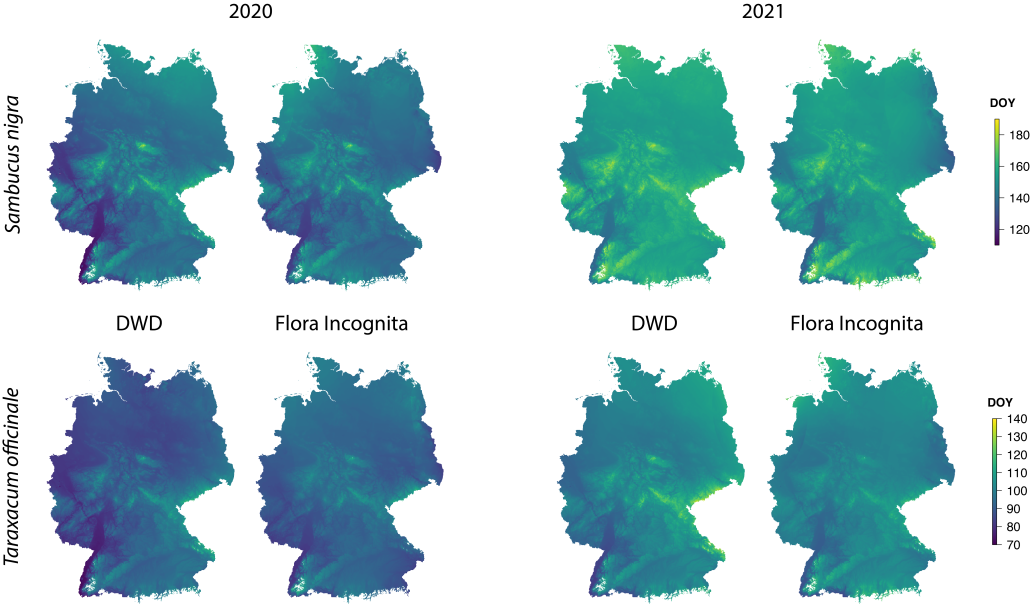

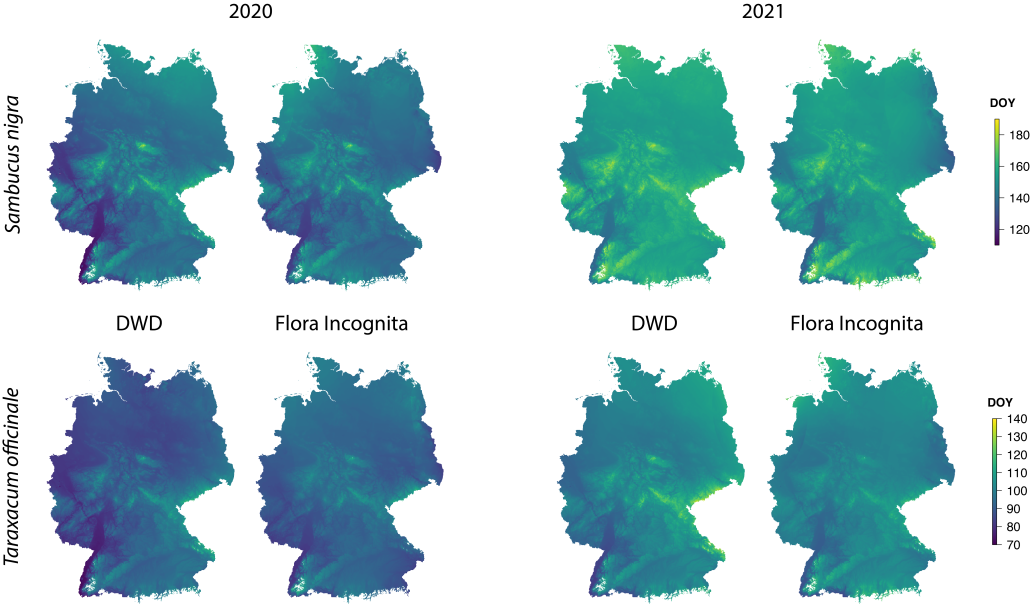

In the next step, the onset of flowering in 2020 and 2021 was calculated for each of these Flora Incognita stations, and the station data was interpolated for the whole of Germany. The resulting interpolation maps show similar results for most species as the manual documentation by the DWD.

Spatially interpolated maps based on the DWD and Flora Incognita stations for the onset of flowering of Sambucus nigra and Taraxacum officinale in 2020 and 2021. The color scale indicates the day of the year of the onset of flowering in each grid cell (from: Katal & Rzanny et al. 2023).

Take-away message

The main finding of the publication is that the onset of flowering can be inferred from our plant observations – at least for annual herbaceous species or shrubs with a conspicuous flowering phase. This means that Flora Incognita data can supplement the traditionally collected phenological surveys on a broad scale, but also for many new species. This allows us to make a valuable contribution to the documentation of phenological shifts, which is of vital importance for the documentation and understanding of climate change, among other things.

We want to thank the many users of Flora Incognita who contribute to this new source of data. It is your curiosity that enables research like this.

The publication is now freely available:

Katal, N., Rzanny, M., Mäder, P., Römermann, C., Wittich, H. C., Boho, D., Musavi, T. & Wäldchen, J. (2023). Bridging the gap: How to adopt opportunistic plant observations for phenology monitoring

Frontiers in Plant Science, 14. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1150956